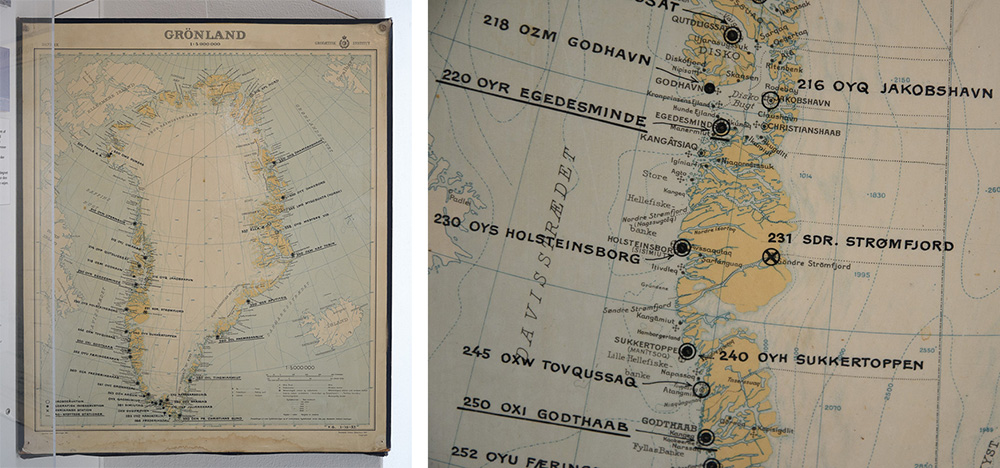

Kangerlussuaq is called Sondre Strømfjord on this 1957 map of Greenland on display on the ground floor of the Arktisk Institut. The map emphasizes the Danish colonial names in bold lettering, with Greenlandic names present, but in a much smaller font. Those Danish names went by the wayside in 1996 and today you won’t see them on a map.

Above: Stig Rasmussen at work in the photo archive at the Danish Arctic Institute (left) and the old stone building where the Institute is housed, formerly used by the whaling industry in the 19th century.

The first part of my trip was Washington Dulles to Copenhagen on a one-stop through Amsterdam. Getting to Greenland — or anywhere in the world — means strategizing around flight availability and compliance with COVID entry rules. In the case of both Denmark and Greenland, only fully vaccinated foreign citizens may enter, but Greenland also requires a COVID PCR lab test, performed within 48 hours of your flight. Since PCR results at the Copenhagen Airport take several hours to complete, it made sense to spend two full days in Copenhagen in between my arrival from the States and departure to Greenland to be absolutely sure I could show up at check in with the required documents. This is the first time I have ever been to the same airport on four successive days — I practically felt like a commuter getting on and off the Metro there every day. And even though I had absolutely no reason to think I'd test positive to COVID, when I finally received the text with the link to the results Thursday afternoon, I've worked so hard to arrange the puzzle pieces of this trip so they'd fall into place at the right moment that my hands were actually shaking as I clicked it. And..."Your test results are negative [green smiley face emoji]." Phew! One last trip to the airport 6:30 a.m. yesterday morning at the Air Greenland queue with all the documents in hand, and flew back across the Atlantic 4 hours and 40 minutes to Kangerlussuaq. I'm writing from my dorm room at the Kangerlussuaq Science Support Center, where I've taken today off to regroup from a few days that's been a mixture of rewarding, enjoyable, tiring, and yes, sometimes very stressful.

However, there were benefits to spending two full days in Copenhagen. Not only is it a picturesque city that I'd never visited before, I had recently found out about the Arktisk Institut (Danish Arctic Institute), a repository of documents, artifacts, and images related to the Danish presence in the Arctic that has, according to its website, "the worlds largest collection of historical photos from Greenland and the Arctic."

Since one of the ideas for my project is a series of "then and now" photos showing how the places have changed in the past several decades, I had arranged an appointment with the photo archivist Stig Rasmussen, to go through the Institute's vintage photos of Kangerlussuaq. He was prepared with my list of sites that I plan to photograph, and walked me through the corresponding images in their collection and how to use their search function efficiently to locate the most relevant images myself. This involves using Danish words as search terms, even while using the English interface — not something that would have occurred to me.

As we went through the photos, he also offered entertaining explanations of the people had taken them and later donated them to the archive. Among the major contributors of Kangerlussuaq materials are Christian Vibe, a biologist who oversaw the reintroduction of musk oxen from East Greenland to Kangerlussuaq in the early 1960s, and Borge Fristrup, a glaciologist who took photographs of the Russel Glacier near the ice cap in the 1950s, which I will be very interested to compare with how it looks now. Numerous photos show the early decades of the joint American and Danish air base. And the jokey red and white signpost I showed in my previous post — "Paris 4 hours 25 minutes," "North Pole 3 hours 15 minutes," etc.? It kept popping up in our searches, apparently having been photographed in every era and from every angle.

Kangerlussuaq was not a permanent settlement for the Inuits of Greenland until the Americans built the air base in the 1940s, but we came across a few photos from the 1920s of families passing through the area in hunting season. These images — and ones from elsewhere in Greenland — are all online, so you can see them yourself at if you're curious. An additional trove of 20,000 photographs — including many of Kangerlussuaq — were recently donated by a Greenland contractor and are currently out being scanned. When Stig receives the digital files later this month the photos will gradually be uploaded to the website over the next year or two.

After we wrapped up in late afternoon I headed to the nearby University of Copenhagen to meet up with Bart Pushaw, an American art historian who has a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Copenhagen. We've both been taking Greenlandic classes for English speakers on Zoom through a Greenland-based school called Learn Greenlandic, but had never met in person or had an extended conversation before. Turns out we have a lot of common interests! Bart is working on a book about on post-colonial art by Arctic people from the 1700s to 1950, including present day Alaska, Canada and Greenland. He therefore given much thought to the processes and ramifications of cultural interactions between Westerners and colonized indigenous people. Those issues are in the mix for my project in Kangerlussuaq as well, though time-wise my project starts around 1950, where his leaves off. Coincidentally, our weekly Greenlandic class met at 5 p.m. Danish Time that day, so we attended together from his office. Although Bart is fluent in a few Nordic languages, he agreed with me that Greenlandic is infernally difficult to learn. However, as I walked around town in search of the supermarket late yesterday afternoon, I at least had enough vocabulary to recognized when I'd passed the school (Atuarfik), and that the abbreviation on street signs Aqq. stood for aqqusineq (road). We'll see if I pick more up just by being here.

As they say in Greenland, Takuss — See you later!